In Emblems of the Mind: The Inner Life of Music and Mathematics (Times Books, 1995), Edward Rothstein talks about musical and mathematical notation as secret symbols, undecipherable by the uninitiated.

“Uninitiated” is a good word for music teachers to remember when working with beginning adult students because that’s how these students feel. They feel a sense of magic about music and they feel ignorant. They are coming into the presence of one who knows this magic and they feel uncomfortable and insecure to a degree most teachers would not believe. Teachers should understand the risk beginning students feel, appreciate their great courage, and be very considerate.

People sometimes confuse reading music with being musical. The ability to read music is very useful but it’s not the same thing as being musical.

Reading is a different skill that involves eye, ear, and hand coordination. If one has difficulty in this area of learning, one could play by ear, play an instrument with less complicated notation than the piano, or explore an alternate form of notation.

How Teachers Can Make Reading Difficult

When a student works with a teacher who is impatient during the early phases of reading notes, the student will feel unnecessarily incompetent. In some cases this is so severe students give up and assume they were just not meant to play piano or worse yet, they aren’t musical.

The power of an earlier negative learning experience is impressive in its impact. I’ve watched students trying to read music who were so paralyzed by their panic and fear of inadequacy they couldn’t even think.

Undoing this trauma takes time and I’ve worked with some who have become so convinced of their own lack of ability that no amount of evidence to the contrary held their confidence long enough to establish a new belief in themselves. They usually conclude that they have no talent and give up.

We all need our own amount of time to learn. Just because someone else wants us to learn faster doesn’t make our own learning speed a fault. In fact, it needs to be honored. The advantage of students hiring a private teacher is to have someone exclusively sensitive to and fit into their own realities. Alas, this is such a novel concept that few students know how to take advantage of it. In our personal history, power was always on the teacher’s side. We forget that as adults, we employ the teacher.

A failure of many teachers, and I’ve certainly been guilty of it myself, is to underestimate the difficulty of note reading with adults. After all, adults can comprehend the concepts of note reading quickly. As discussed earlier, understanding concepts is not the same as putting that into action. It’s transferring the concept to being comfortable with physical act that takes so long to learn. (See The Fossil Mind of Concepts.)

When teachers don’t fully appreciate this difficulty, they give their adult students pieces that are too difficult. Students become frustrated, never learn to become at ease with the instrument, and are so close to the edge of their maximum effort that being musical is a luxury. If students try to publicly perform these pieces, it usually results in disasters that make students miserable and reluctant to perform again.

Teachers incorrectly see the adult students’ failure to master these too-difficult pieces as evidence that adults can’t learn.

What’s Note Reading?

What does it mean to read music? Most teachers never ask the question because it’s second nature to them. It’s assumed just like reading words.

What do new students think reading music is? Teachers seldom ask and we should ask because students have their own assumptions.

Frequently these assumptions get in the way and teachers never realize the problem.

It happened again today with an advanced elementary adult student who announced during her playing, by way of confession it seemed:

“You know, I’m not reading the notes.”

“Ah…excuse me?” said I.

“I’m not reading the notes.”

“Then how are you playing the piece? I know you’re not doing it from memory,” I said.

“Well I don’t have any idea what notes I’m playing,” she said.

“Then how are you playing them?”

“Well, I’m just playing by the feel.”

It’s an interesting contradiction. She didn’t know what notes she was playing yet she played the right notes. The solution to the contradiction is that she thought note reading was supposed to be naming the notes. It’s not. I rarely know the name of the note I’m playing. I could always stop and figure them out, but really, the note names are irrelevant. Nobody cares. The audience cares about the sound and the performer cares about the sound and about the sensations under the fingers. One could say it’s playing by ear using the eyes.

At the beginning stages of learning to read music naming the notes may be useful just as naming the letters in “cat” is useful to an early reader of words. In time, however, the group of notes becomes the unit the same way more experienced readers perceive the word “cat” as a single unit rather than three units.

What is Note Reading Then?

Note reading is about sound and shape and feel of the hand. Students tend to think of reading as eye-hand coordination but that’s only part of it. Ear-hand coordination is equally important. “What does what I see sound like?” Then, “what do I do with my hand to make it sound like that?” It’s guessing what the next sound is and playing it.

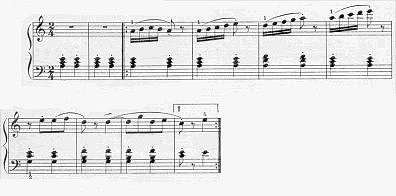

Another part of reading is seeing the visual relationships. Is the note higher or lower and by how much? Of course, it could be the same. There are patterns to be seen that can make reading easier. Let me use an example–Arabesque, by Fredrich Burgmuller. It’s a simple example but it will show the way:

In the left hand, the notes are the same for four measures, then the upper two notes each go up one note higher as the bottom note stays the same, then they return to their starting point for one measure. In measure 7 the lower note drops down one while the upper two notes stay the same. In measure 8, the upper two notes expand with the upper going one note higher and middle note going one note lower as the bottom stays the same.

There is no reason to verbalize these relationships as I’m doing here. It is only necessary to see the relationship and move the hand accordingly.

When the right hand begins, it goes up three notes and then back down to the starting note. In measure 4, it starts on the same note and goes up five notes. Measure 5 starts one note lower than measure 4 ended and again goes up five notes. Measure 6 begins on the note measure 5 ended and again goes up five notes.

It’s these visual relationships that are so important to see and they have nothing to do with naming the note.

An Observation

Notes are a series of points. These points are very deceptive because musical sound is not a series of points. Music is a continuous stream.

Notes are like discreet math. They mark points along the way. Music is more like calculus. It’s what happens between the notes that counts. The magic of music comes from the way one note flows into the next. What happens between the notes, between those little dots, is what makes real music.

Pity the poor pianist. He can do nothing between the notes but let them do what they will for the piano is as a percussion instrument and the notes inevitably die away without any possibility of intervention by the performer except to prolong the note until it dies away into silence. We envy the string players, the singer, the woodwind and brass players for they can do so many things with the sound between the notes. The can get louder or softer with great and subtle variation. Many can do vibrato to liven up the continuing sound. Pianists can do nothing. I remember talking with a violinist friend who spoke of his great admiration for the imagination of pianists. He was impressed by their ability to imagine the sound of a crescendo on an instrument where the sound of each note can only die away.

It is through this imagination that pianists conceive of and communicate the continuous evolving shape and tension of musical phrases. It’s through this imagination that pianists surmount the little dots on the page and the limits of their instrument.

An Alternate Notation

Some people find conventional notation a huge stumbling block to learning to play the piano. An interesting and successful alternate is Klavarskribo. Klavarskribo, which is Esperanto for keyboard writing, presents written music as a horizontal image rather then a vertical one like conventional notation. The result is that a higher note is further to the right and a lower one further to the left as it is on the piano. The notation matches the view of the keyboard instead of having to be turned ninety degrees.

Rhythm is expressed vertically with the lines running top to bottom. The duration of a note is an expression of the space a note occupies rather than its color.

In Klavar notation, the lines and spaces represent the black and white notes of the keyboard. Black notes are black keys and are on lines and white notes are white keys in the spaces. A picture will make this clearer:

While my own experience is limited, I want to make two points.

The first is that significantly less teaching words are necessary for a beginning student to understand and start playing. It is much more accessible.

The second point is an example of a very bright, successful 13 year old who played the Bach Invention in d minor at my last student recital. I asked him to try the Klavar notation from the progressive Hal Leonard Student Piano Library series. Within 45 minutes he was in Book V playing pieces he never seen before. He said he found it a much easier system to read. I asked him if he would rather have worked on the Invention that way and he quickly said yes that it would have been easier to learn. That a successful student found this system easier to use after 45 minutes than the conventional system after four years says something that should not be ignored.

The biggest limitation of the system is it has to be ordered from Europe and that takes time and adds cost for people in the New World. Another limitation is that not all works are available in Klavar, currently only about 25,000 can be ordered. You can, however, transcribe music yourself by hand or by computer.

To get further information about Klavar, go to the Klavar Music Foundation of Great Britain.

There are other alternate notations but I have no experience with them. Information can be obtained by going to the Music Notation Foundation.

I am an old age pensioner and I have just started to learn music and playing a keyboard I have some experience in playing music in the do ra me fa so la t do but I have difficulty in learning the music scale such the abc and chords I would appreciate it if you could give me advice on learning the scale in an Easie way I am prepared to put in the practice if I understand the system I am trying to learn thank you for your considerationn in this matter